by Julian Baker | May 30, 2020 | Uncategorized

Recently, I have heard a lot on the idea of the psoas being able to harbour trapped emotion. Forgive me if my view is a little tongue in cheek but if you’ve watched our webinars, you’ll already understand how I look at things a bit differently.

Recently, I have heard a lot on the idea of the psoas being able to harbour trapped emotion. Forgive me if my view is a little tongue in cheek but if you’ve watched our webinars, you’ll already understand how I look at things a bit differently.

If muscles were people, then the psoas would be the head of the football team, rugby team or cheer squad. Vacuous and emotionally stunted, whilst looking great. Muscles in general have one thing to do which is contract and relax. They are brilliantly equipped with their own cells and motor units and each muscle is considered an individual organ. What they are not capable of is memory. Although the idea of cellular transference and cellular memory is a thing, muscles themselves are power houses and I don’t believe in any idea of ‘muscle memory.’

Instead, what is clear is that nerves that are myelinated, having laid down fatty schwann cells, will transfer information faster via a process of it jumping over spaces, nodes of Ranvier, created by the myelination of the nerve. This jumping is called saltatory conduction after the Italian saltatore – to jump. Myelination of nerves comes about as a result of learning something. The more you do something the better you get at it, not because the muscles have learned anything, but because the nerve endings that deliver the information from the brain have become finely tuned to the job required, be it playing a trumpet or juggling chainsaws.

The area around the psoas is a hugely loaded area from many respects and the psoas fits in within a chain of other structures to do a job. The central location of this area being around the solar plexus suggests that it would be a central point for emotional responses based around the autonomic nervous system. This is an area that will need to have rapid response in the case of sympathetic nervous system responses, with the pancreas being involved in triggering hormones to release energy and for the digestive system to restrict blood supply and so forth. The psoas just happens to be there.

However, I do feel strongly that as highly emotional beings we don’t primarily respond mentally to our emotional input but instead go to the physical as an initial response. We don’t think angry, we feel angry, we feel sad, we feel stressed and so forth. Our language expresses this perfectly. Our thought processes come along and we start to think our feelings. For most people this is the problem and one of my workshops called Emotional Stiffness, discusses the idea of us being physical and emotional beings before being mental and thinking beings. What does ‘angry’ look like?

It’s not hard for us to look at someone else and say that they look angry, sad or stressed. As well as their behaviour there are physical signals being given that alert us to the emotional and, by extension, mental state of an individual. We use these senses all the time with ourselves and with others without being conscious as to what our physical form is doing to reflect or represent our emotional state. We have trained ourselves into these physical states since early childhood. We know what angry feels like in our body and we know what to do with our body when this feeling arises. As well as the physiological changes that we know about and can measure in the sympathetic nervous system such as heart rate, breathing, blood flow and so forth, we will have learned to adopt a physical position. It’s a go to that will happen every time the emotion, whatever it might be, is triggered. Learned behaviour is a training as sure as weightlifting or yoga is a training and we will lay down connective tissues around our muscles that will support this and allow us to adopt that position when we feel the input that directs the feeling.

If we have spent many years being angry, depressed and so forth, we will also have trained our physical form into an instantly familiar pattern that will reflect our emotional state. In time the physical state becomes inseparable from the emotional state and one potentially drives the other. The cycle is indivisible unless it is recognised. We might spend a lot of time with our therapist, recognising our patterns, understanding our behaviour, recognising our triggers and dealing with our behaviours, but if our physical behavioural patterns are strongly embedded, then just by moving into a certain position could have the potential to move us into the familiar emotional state that we are trying to step away from.

My aim in my workshops is to help people to start to recognise where in their bodies they experience emotional triggers and what happens to their body as a response. It’s a combination of movement and mindfulness that encourages people to assimilate recognise and where possible allow and welcome their feelings as manifesting in a physical form and then to avoid moving into a mental space that then just spirals downwards.

The bottom line is that it’s physiologically implausible to suggest that one muscle or even a collection of muscles for that matter, can ‘store’ memories. What they can do is respond to and easily move into a position that is familiar. Focussing on one muscle or structure is never either useful or correct and the idea of individual muscle function is a contradiction in terms. I believe that building integrated understanding of how we affect and influence our function from a physical, emotional, social and mental perspective and create imbalances in health and ill health, allows us to make much smaller and more manageable steps towards addressing dysfunction or imbalance.

by Julian Baker | May 15, 2020 | Uncategorized

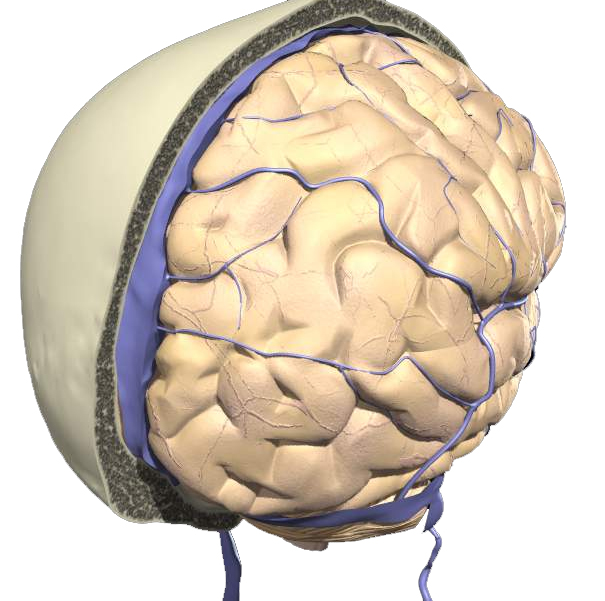

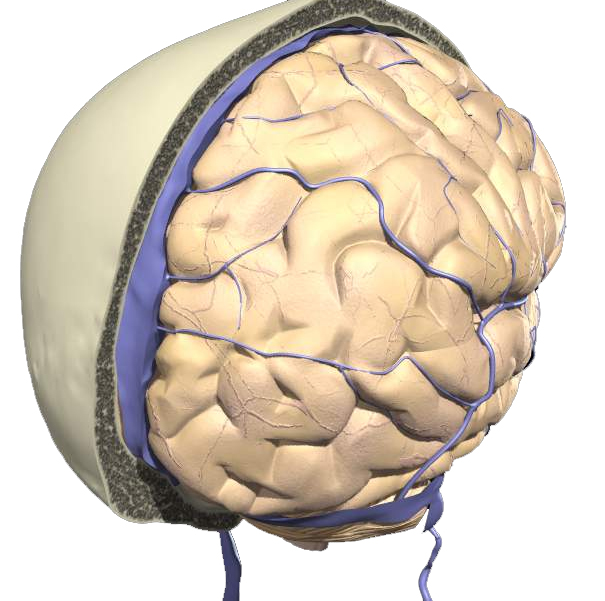

The Saggital Sinus

In mentioning that I was planning a future webinar on spinal cord, dura and meninges, I was contacted with some brilliant questions and thoughts about cerebrospinal fluid and the effect that therapies such as Cranio Sacral Therapy might have. The theory around the techniques suggests that movement of the cranium in clockwise and counter clockwise directions, influences and improves the drainage from the sinuses into the carotid veins. There is a popular understanding that congestion of the CSF can occur secondary to trauma or dental work.

I will admit to knowing not much about the application of the techniques, although I have been on the receiving end of them many times. I have found them to be pleasing and useful especially during a phase when I was experiencing severe headaches. I have also known many people who have had their babies and young children treated with cranial techniques to very good effect.

However my personal feeling is that it is unlikely that the work being done by these therapies is having a direct, mechanical effect on dura or CSF. I just can’t see it. In the fully formed adult head cranial plates don’t move to a degree that can be palpable or affected by the type of pressure usually associated with manual therapy, and neither should they. The sutured plates are there to give a birthing baby the chance to pass through the birth canal without destroying its mother in the process. Once this has been achieved, the necessity for the plates to move isn’t there, and instead the more important role of hardening and fixing to protect the fragile contents of the skull begins.

Unlike the sacrum, the skull also doesn’t need to transmit load or force through it and indeed if the kind of forces generated through the sacrum were applied with any degree of regularity to the skull, brain damage would soon follow. In an infant I do appreciate that this application would have a different perspective.

The incredible thickness of the skull, even at its thinnest area, therefore renders the likelihood of direct effect on the dura or meninges unlikely in my view. However if we are talking about the power of touch to inform every aspect of human behaviour, then all bets are off in terms of what is being achieved.

Putting hands on anywhere, brings an awareness, not just to the localised area being touched, but to all the other areas that are connected to, associated with or affected by the place we are touching. Most of these associations would not be conscious from the client perspective or intellectual from the therapist perspective, in terms of anatomical or theoretical connections established through research or study.

Instead these connections are things like the time we fell off our bike, banged our head and twisted our ankle and spent two hours in the nurses office gagging to the smell of Germolene and feeling nauseous. The resulting associations embedded in this experience become part of our physical, mental and emotional psyche and are impossible to untangle or even identify from either side. The touch that brings all these together even if these realisations are still unconscious, allow a shifting of behaviour and a change of focus of pain or sensation. More information is put in to the existing embedded memory and pattern and more information allows for greater integration of personal experience, good or bad.

There is considerable resistance to the idea that we aren’t actually doing what we think we are doing or what we want to be doing. The clinging to belief, personal conviction, original training and even research papers, sometimes presents barriers to letting go of strongly viewed theories. I will get told many times in no uncertain terms, that I am wrong. That these things do move and that X, Y or Z is happening and that you can feel it under your hands. Well maybe you can, and I for one have no doubt that things happen in sessions that are way beyond what we can reasonably explain using anatomy, physiology or science of any kind. All I can do is present what evidence a donor gives me and what I see. Also logic should prevail to some degree as well. We know that touch is a powerful promoter of change in every aspect and sense: physical, mental, emotional.

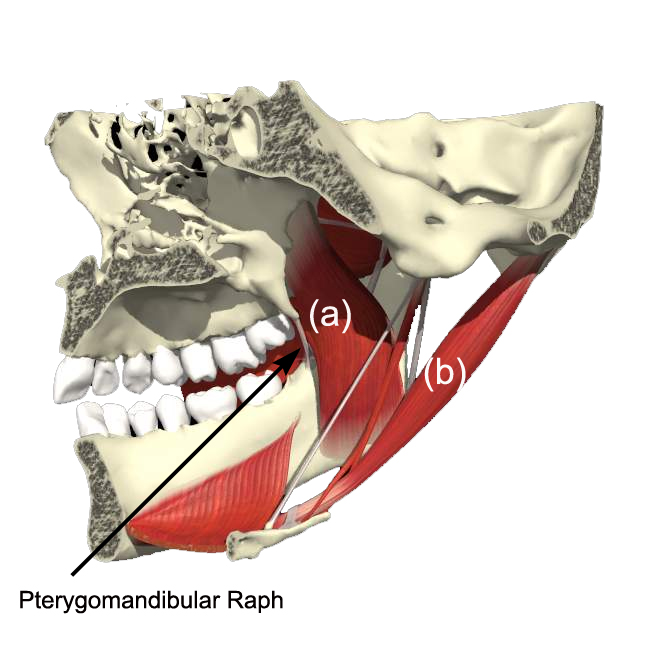

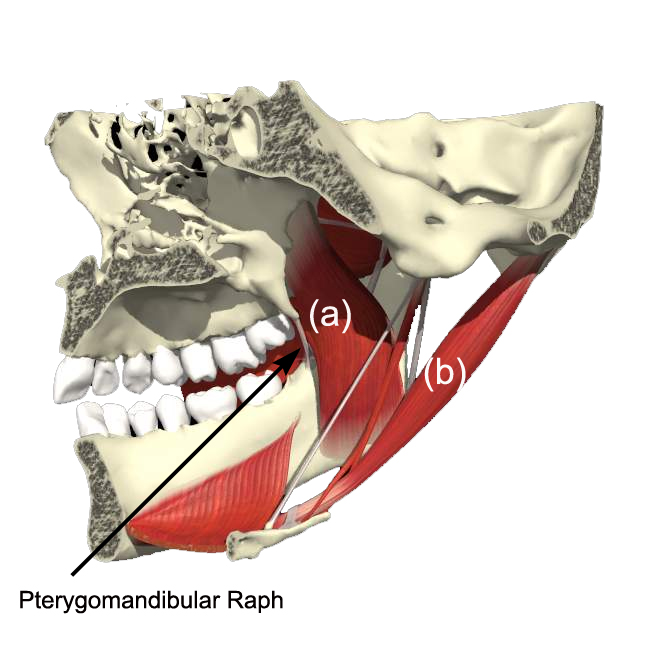

The Pterygomandibular raphe. Still a good distance from either of the actual pterygoids.

The jargon and regularly applied phrases such as ‘dural release’ and ideas around working the pterygoid plates come up and it’s hard to find meaning when looking at either how accessible (or inaccessible) any of these structures are in reality, or what ‘release’ might even mean. There’s no doubt that working in these locations will bring proprioceptive awareness to the area, but as to what release actually means is anyone’s guess.

If within this filed we recognise the need to influence fluids, then I would suggest that it is not just CSF that is worthy of our attention, but indeed all the wet bits we possess. Therefore I once again come back to the importance of movement and within the movement, the need to create compression and apply compressive forces within the movement, such as squatting or resistance within and as many ranges of movement as possible. It is these forces, applied regularly and with as much variation as possible that I believe helps effective fluid circulation and is going to be more effective than any physical force that a third party can apply to a body. However the need for an individual to have the ability to create awareness and focus on areas of their body where movement is restricted, painful or where the acquired lifetime patterns of movement and no movement, have introduced limitations that hold us from moving to our fullest potential. This is the unique ability that touch confers,

The right touch, in the right place, with the right story, from a compassionate, caring and insightful therapist is something that no amount of science will ever compete with.

Recently, I have heard a lot on the idea of the psoas being able to harbour trapped emotion. Forgive me if my view is a little tongue in cheek but if you’ve watched our webinars, you’ll already understand how I look at things a bit differently.

Recently, I have heard a lot on the idea of the psoas being able to harbour trapped emotion. Forgive me if my view is a little tongue in cheek but if you’ve watched our webinars, you’ll already understand how I look at things a bit differently.